by

Kathleen Ann Goonan

The Jehu

Road to Gorka

by

Kathleen Ann Goonan

The only information we had about Gorka was a little tale in our guidebook: during WWII, the British asked a Gorka infantry division for volunteers to be dropped behind enemy lines. Half stepped forward. The captain began to explain how to use the parachute. One Gorkan asked "You mean we could use parachutes?"

The rest of the division stepped forward.

We went to Gorka because we

wanted to see Nepal and had only one day to do so.

After an early

hourlong mountain flight to see the Himilayas, we were met by the

English-speaking guide we had bargained with the previous

afternoon to take us, provided he could find a trustworthy

vehicle. "New," he had promised. "Strong." As

far as I could tell, Kathmandu received a shipment of Toyota

Corollas ten years ago. Each car has been scattering pedestrians

and dogs in narrow, rutted lanes full time since. I saw no new

cars, and hardly any that were not faded, dented, ragged-out

Toyotas. Considering the bone-numbing driving conditions, this is

an impressive testimony to their durability.

After an early

hourlong mountain flight to see the Himilayas, we were met by the

English-speaking guide we had bargained with the previous

afternoon to take us, provided he could find a trustworthy

vehicle. "New," he had promised. "Strong." As

far as I could tell, Kathmandu received a shipment of Toyota

Corollas ten years ago. Each car has been scattering pedestrians

and dogs in narrow, rutted lanes full time since. I saw no new

cars, and hardly any that were not faded, dented, ragged-out

Toyotas. Considering the bone-numbing driving conditions, this is

an impressive testimony to their durability.

Our taxi was the most battered piece of rolling metal I'd ever seen. Special pressures had to be applied to the window cranks to operate them, and my door didn't open from the inside. In the US, these cars would have been junked long ago.

Our guide, Barhrat, was a short, thin young man with an intelligent grin and a red kohl smear on his forehead. "New car," he said, thumping the hood. From the dark interior, the driver nodded fiercely.

"This will make it to Gorka?" my husband asked skeptically.

"No problem, sir," replied Bahrat. "Strong car."

We envisioned the row of tight connections which we had to make in the next few days collapsing like a row of dominos as the strong, new car sputtered to a halt in Nepalese wilderness. But momentum won. Abandoning caution, we got in.

Heading west out of Kathmandu, we halted frequently for the water buffalos which wander dusty lanes. The city looked curiously half-finished to our Western eyes. Small, flat-topped buildings straggled to a halt after two or three stories. Every hundred yards or so was a big, dusty pile of bricks, suggesting that when the need arises, the sturdy Nepalese grab some and add another ragged story.

At the top of the pass to Kathmandu's west, we asked the driver to halt so that we could take a picture. He obliged, and immediately slid under the car and began banging on something.

"Is the car broken?"

"No, sir," grinned Bahrat, lighting another cigarette. "New car, strong car."

After that pit stop, the car was invigorated. We flew down the one-lane, hairpin-curved, cliff-edged, truck-infested main road to India, passing on blind curves, and came to a disquieting realization. We were in the hands of a the hands of a bona-fide card- carrying jehu.

Jehu? Remember it. It's a useful, true word.

Jehu was a king of Israel noted for his furious chariot attacks. Thus, a jehu is "a driver, especially of a cab or coach; one who drives fast or recklessly".

All the drivers in Nepal are, of necessity, jehus. Drivers of trucks, drivers of overflowing busses, drivers of ten-year-old Toyotas. It is the style.

"Slow down," I shouted. He and Bahrat were perfectly relaxed in the front seat, playing Hindi tapes and smoking cigarettes, reveling in a high-paid day out of town. Bahrat protested, "Gorka is far." It was fifty kilometers away.

"It's ok if we don't get there."

He spoke to the driver, who glanced in the mirror, laughed, and complied.

At the bottom of the pass, we paused at a one-lane bridge.

And entered a different world.

To the right, a thin man struggled through thigh-high water, holding his plow steady behind two water buffalo. Near him, three women bent, planting rice. We passed the first of many foot travellers. A sturdy, handsome woman in a flowing purple skirt strode westward carrying a huge basket by headband. Bands of bare soil and vegetation alternated on the terraced mountains.

Guana turned. "Cigarette with Nepalese tobacco?" We declined. As the day passed, and he indulged in Nepalese tobacco more often, his English deteriorated markedly.

I was unprepared for the bone-jolting properties of this "main highway", built by India in the early seventies. We left the paved part shortly out of Kathmandu; although pavement returned fitfully during short stretches, the road is generally deep ruts. This does not appreciably impede traffic, which is heavy and consists mostly of overflowing busses and gaily painted heavy trucks which head straight for one another in a routine game of chicken. We saw several instances in which no one chickened out, and the trucks whose corners kissed were left in the center of the road while the drivers presumably rambled off to discuss the problem over a few Star beers.

The Universal Law of Jehuism: Never give an inch. The Unalterable Law of the Horn: Use it. Constantly.

"Please Honk Horn" is painted on the backs of most large vehicles, and our driver was happy to oblige, just before passing on blind curves. As he did, the type of memory that people pay analysts handsomely to unearth surfaced: Three kids cower against the back seat floor hump of the '56 Chevy as dad squeezes the car between passee and oncoming vehicle.

Our driver's face in the rear view mirror merges with my father's. The narrow-eyed expression of cool concentration is identical.

Soon the road met the Marsyangdi River, a clear green ribbon that cuts through white sand flats. Here and there black cattle drank. We saw a few rafting parties which stopped for lunch.

During the first hour, it was nap time in Nepal. Women dozed on wood banches on porches, enfolding babies protectively. Somnulence reigned. Dogs and pigs rested in the shade. Gauna informed us, "We'll stop for lunch in Muglin," two hours away.

In Kathmandu, we had paid for a one-day pass at

a tiny ramshackled building where business was conducted on the

front porch. Getting the pass took half and hour and 200 rupees--about $10--at

a building in Kathmandu where business was conducted on the front porch. At

the first checkpoint, we made a swift turn--in front of an oncoming truck, for

extra points--and halted with a jerk in front of a wooden shack. Guana jumped

out and ran up the steps, where a soldier with a gun examined our "pass."

There were frequent checkpoints. In Nepal, they like to know where you are.

In Kathmandu, we had paid for a one-day pass at

a tiny ramshackled building where business was conducted on the

front porch. Getting the pass took half and hour and 200 rupees--about $10--at

a building in Kathmandu where business was conducted on the front porch. At

the first checkpoint, we made a swift turn--in front of an oncoming truck, for

extra points--and halted with a jerk in front of a wooden shack. Guana jumped

out and ran up the steps, where a soldier with a gun examined our "pass."

There were frequent checkpoints. In Nepal, they like to know where you are.

Nepal's poverty generates sad statistics. Half the children die before age five, presumably from lack of medical care. But surely some are killed along the violent India road, where the porches edge directly on the road. And since the road is often the only flat land around, social interaction takes place there. Children play, dogs and pigs forage, adults travel relentlessly on foot with their overwhelming burdons, and heavy traffic thunders through the midst of this, with a warning blare but without appreciably slowing, at frequent intervals. Our driver scattered the brass bands of funeral and wedding processions without a backward look, without a tap to the brakes.

Nepal is poor. The average Nepalese makes $120.00 a year. Literacy is 20% for men; 5% for women. Electricity is rare. As we went deeper into the country, I wondered what they knew of the world outside their medieval kingdom, where the soil is depleted and life expectancy is 47 years.

Outside of Muglin, we stopped at the checkpoint, then pulled into the main town.

Muglin is full of "hotels". The faded signs announced the names in English: Blue Himalayan; Mustang. From the second story of rickety buildings, ragged, faded curtains blew out of low windows. We followed our driver into dark room with a few tables and went out the back door to the privy. From there we could look down into the kitchen - a dirt courtyard where a cluster of fly-laden dishes, full of food, sat uncovered awaiting consumption.

Lacking gumption, we wandered into the street, importuned by sweet-looking begging children. I bought a soda and a box of cookies from a couple who ran their snack bar from a waist high platform where they sat crosslegged among their packages of biscuits and bags of chips; I dispensed most of them to the children. Sewage laden water puddled the road. An impromptu brass band gathered and wailed Nepalese jazz: free-form, join in when you please. A crowd gathered, clapping, smiling, in the hot sun. The people were all very friendly, very kind.

"I have to have rice every day ," said Gauna as we climbed back into the car. The driver snapped on the Hindi tapes, and we were off again.

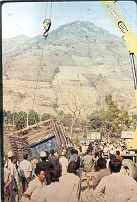

But right outside town we were

the first to be halted by a rescue mission: a crane recruited

from a nearby Chinese dam- building project was righting a truck

which had rolled off the road. It took only twenty minutes, and

everyone from Muglin congregated and milled about. I got the

impression that it wasn't an unusual sight.

But right outside town we were

the first to be halted by a rescue mission: a crane recruited

from a nearby Chinese dam- building project was righting a truck

which had rolled off the road. It took only twenty minutes, and

everyone from Muglin congregated and milled about. I got the

impression that it wasn't an unusual sight.

Soon we came to the junction to Gorka, and passed through a village. Store owners squatted on porches, eyeing us. We turned north, and to our surprise, the road was well- paved. We glided upward on a luxuriously smooth ribbon of asphalt. The villagers we passed always turned with a look of astonishment on their faces: clearly a car was an unusual sight. Houses changed; instead of yurts and shacks, they were made of brick; neat, clean, rural. Away from the road to India, Nepal regained self-respect.

Gorka? A small bazaar; dinner cooking on braziers. Mountains remeniscent of the Smokies stretching blue and high all around. We didn't hike up another mile to try and see the Himalayas because it was late in the afternoon and probably too hazy to see them. I bought a soda in someone's kitchen; the man ran across the road to get change. There were two little boys; one about five, one two. The two-year-old walked up to me; his hands met in front of his chest. "Namaste," he said. "Namaste," I replied, bowing my head.

He laughed delightedly, and his big brother's eyes got very wide. Taking advantage of an unexpected audience, they began to show off by fiddling with a pot on the stove; their mother scolded from the back room and they desisted. The man returned with his change and our car arrived from down the street where the driver had finally dealt decisively with the muffler, and we rolled down the smooth road.

As we came into one village, a crowd had gathered around a large log which squarely blocked the road. We halted. Bahrat shouted, shouts were returned, and the log was rolled away. We proceeded.

"What was that all about?" I asked.

"They said the bus hasn't been stopping there and they wanted to make sure it stopped this time."

Muffler clanking once more, we headed back east. The pair in the front seat were well-known; at several towns friends greeted them and chatted through the window. As it began to get dark, we saw the rafts and bright tents of river-trekkers at river's edge.

"We will stop for tea," our driver said at twilight, and pulled up to a shack. The front porch was supported by crooked sticks. The cooking facilities were generally stone or brick fireholders topped by a grate. Here, a pot of tea boiled furiously on the fire.

Relieving oneself in the outlands of Nepal is generally not accomplished in places specially set aside for only that. Looking for a suitable location, I crossed the road. Below, a path led down to the river. Grinning up at me, an old woman kicked a rock off the path and squatted. An inhibited Westerner, I began to climb the hill behind the teahouse. Looking back, I saw an entire truckload of laborers looking upward expectantly. I climbed on.

When I returned, a beautiful woman with dark, smiling eyes handed me a glass of hot, sweet, milky tea in a small glass. She was dressed in an ornate black sari, and nodding toward me, she exchanged a few words with other women there. They looked at me and broke into friendly laughter, presumably aimed at my shyness.

Then we were jolting again. It was night, and heavy trucks were still bearing down on us.

"Do the headlights work?"

Our jehu apparently thought them an unecessary affectation, but turned them on to humor us.

Some of the dark villages seemed deserted. Ladders, not previously in evidence, led to the second floor of many of the buildings. No interior stairways. The residents of these towns retired early. Presumably, illumination was a luxury here.

In other villages we threaded our way through a maze of trucks parked on the road. Kerosene and gas lanterns shone on porches; lively music issued from hotels and cafes, swallowed swiftly by distance as we jolted our way to Kathmandhu.

Near the pass which led back over the mountain, we saw the first sign of civilization: lanterns gave way to bare electric bulbs. And the roads became blessedly smoother - or perhaps we couldn't go so fast. I was growing quite accustomed to jehuism. I could appreciate its necessity by the time we returned to The Blue Diamond Hotel.

Road manners differ everywhere. Westerners stick primly to their side of the road, signal their intentions, follow the rules.

In Asian cities, masses of jehus battle for space. To signal one's intention is to lose the advantage.

And in Nepal, we experienced frontier jehuism at its finest. China, India, and Germany diligently improve roads, generate electricity, oversee breweries. But Nepal remains medieval, mysterious, its people lacking the rudiements of medicine and literacy, its land farmed out. There is real grounds here for misery, yet most of the people we met seemed cheerful, even happy. And it does have one remarkable advantage.

Here one can recieve top-notch, hands-on training in the Ancient Art of the Jehu.

Originally

published in the Washington Post

Copyright © 1987 Kathleen Ann Goonan

All Rights Reserved.